This post is a bit different from my normal posts as I’m tackling a serious topic that isn’t discussed enough in geekdom–the portrayal of victims in SF/F.

My grandmother, a retired teacher, taught me to read and write a pinch before I was three. I read through the typical Dr. Seuss and by six, graduated on to books like Howliday Inn and Tales of the Fourth Grade Nothing. I devoured my fair share of Nancy Drew and The Hardy Boys, plus a little Shakespeare and Twain thrown in the mix.

My first foray into writing was a short children’s book called The Fish and the Lion, which was published when I was five as part of a literacy study at the University of Florida. It’s not an exaggeration to say that by 5th grade, I was well-read and well-written for my age.

Despite this, I was oblivious to the world of science fiction and fantasy. It wasn’t until middle school that I discovered the joys of Tolkien, McCaffrey, LeGuin, and Feist. Cliché as it sounds, reading was an escape for me—more so than most as I grew up in an abusive home.

Readers look for a piece of themselves in characters. How much we identify with those characters is directly proportional to how much enjoyment we get from a literary work (even in books with main characters of questionable morality). My favorite books as a teen were those featuring strong female protagonists who strove to achieve their dreams against staggering odds. Problem was, these books were few and far between. Even books with female authors carried their fair share of sexism and Mary-Sues. As I grew older, a depressing pattern emerged in the speculative fiction genre.

Abuse victims, especially those that were female, were written in one of two ways:

- They remained with their abuser, with the implication that they were too weak or too stupid to escape

OR

- The trauma of being abused would cause the development of magical powers in said victim. The victim would then “have an accident” and use those new, uncontrollable powers to kill or harm the abuser, thus leading to their “escape.”

While seemingly insulting, the first method is often true. Survivors often feel that they can’t leave. Who else would love them? Take care of them? Sometimes the victim believes that if they leave, the abuser will harm themselves or others (possibly the children). Worse is when the victim has tried to leave before, but returned because the abuser always finds them.

In the second pattern, the victim relies on magic as a crutch. Rather than leaving through his or her own strength, the character must be rescued by some magical force.

The first novel I read that followed this trope was Arrows of the Queen by Mercedes Lackey. In the beginning of the book, Talia suffers at the hands of her abusive family. When she hides in a tree, a magical horse (Companion) rescues her. Afterwards, she finds herself in possession of great powers, which negates the necessity of ever returning home to her abusive family. I enjoyed the book as a young reader, but I really wanted Talia to face her parents. I wanted her to rage against their abuse or prove how wrong they had been about Heralds.

The first novel I read that followed this trope was Arrows of the Queen by Mercedes Lackey. In the beginning of the book, Talia suffers at the hands of her abusive family. When she hides in a tree, a magical horse (Companion) rescues her. Afterwards, she finds herself in possession of great powers, which negates the necessity of ever returning home to her abusive family. I enjoyed the book as a young reader, but I really wanted Talia to face her parents. I wanted her to rage against their abuse or prove how wrong they had been about Heralds.

Another example would be Stephen King’s novel, Carrie. The protagonist (Carrie) quite literally uses her magical powers to escape her abusive mother and the bullies at her school. While I’d wanted Talia to fight back against her abusers, Carrie took it to an extreme that even I, as a victim, couldn’t justify. I continued reading in search of someone who’d fit some type of middle ground and be more like me–someone who just wanted a way out.

Another example would be Stephen King’s novel, Carrie. The protagonist (Carrie) quite literally uses her magical powers to escape her abusive mother and the bullies at her school. While I’d wanted Talia to fight back against her abusers, Carrie took it to an extreme that even I, as a victim, couldn’t justify. I continued reading in search of someone who’d fit some type of middle ground and be more like me–someone who just wanted a way out.

Even my teenage writing idol, Anne McCaffrey, falls afoul of the pattern. In Dragonsong, Menolly escapes her abusers through magical fire-lizards. Her discovery of these creatures leads to her being swept up by dragonriders and later, to the Harper Hall. With the discovery of her musical talents, she’s never forced to return home again. Once again a character is rescued, and magic saves the day.

Even my teenage writing idol, Anne McCaffrey, falls afoul of the pattern. In Dragonsong, Menolly escapes her abusers through magical fire-lizards. Her discovery of these creatures leads to her being swept up by dragonriders and later, to the Harper Hall. With the discovery of her musical talents, she’s never forced to return home again. Once again a character is rescued, and magic saves the day.

Like most young abuse victims, I thought I’d brought the abuse upon myself. If I left, it would kill my father. After all, he loved me. He didn’t mean to lose his temper. As a teenage reader, the patterns in speculative fiction worried me. With no magic existing in the real world, how would I escape? Could I escape at all without the help of strangers?

In speculative fiction, there were plenty of brawny men and women rescuing the weak and slaying creatures out of nightmares, but so few novels showcased empowered characters shedding their victim status as they escaped—characters who later grew into tough survivors on their own merits. Where were the characters representing me? Where were the role models to show me how it was done?

I spent the majority of high school writing stories featuring young protagonists who used magic to escape horrific situations, particularly abusers. I wrote what was modeled for me, but writing these stories was my own way of searching for answers. How could I become the strong woman I wanted to read about? With the help of friends who cared, I found the strength to leave and later, forgive. Reconciliation required a different strength and taught its own lessons.

As an adult, I’m still inundated by stories that rely on tired magical escapism to carry their abusive victim characters away from harm. Writers struggle to create realism without relying on clichés and tropes.

Take a look at the popular Twilight series and its fan-fiction successor, 50 Shades of Grey. In the prior, Bella doesn’t leave her abuser and is portrayed as too weak-willed to do so. Love isn’t manipulation and stalking, yet she’s so in love with her abuser, she’s willing to kill herself rather than be alone. 50 Shades brings rape into the equation with its inaccurate portrayal of BDSM.

Take a look at the popular Twilight series and its fan-fiction successor, 50 Shades of Grey. In the prior, Bella doesn’t leave her abuser and is portrayed as too weak-willed to do so. Love isn’t manipulation and stalking, yet she’s so in love with her abuser, she’s willing to kill herself rather than be alone. 50 Shades brings rape into the equation with its inaccurate portrayal of BDSM.

In Song of Ice & Fire (Game of Thrones series, Book I), Daenerys falls prey to some serious Stockholm syndrome with her brother and her husband (from a forced arranged marriage), but magical dragons save the day. They (mere eggs in book one) give her strength and courage, which she uses to control her abusers and get what she wants. In the Harry Potter series, Harry is abused as a child/teen by his aunt and uncle until magic (via Hogwarts and Hagrid) saves him.

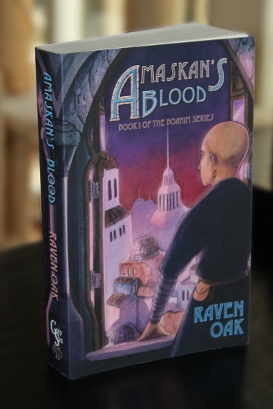

When I wrote Amaskan’s Blood, I had a chance to take this crutch and break it into kindling. I had a chance to get it right.

When I wrote Amaskan’s Blood, I had a chance to take this crutch and break it into kindling. I had a chance to get it right.

One of the major characters, Princess Margaret, suffers at the hands of domestic violence. She’s quite the pain in the ass and whiny to boot through the first half the novel. It’s intentional and part of her arc as she encounters life changing events, including an arranged marriage and an Amaskan bodyguard. In the first half of the book, she’s a victim. As she grows through her story arc, she finds the strength to deal with the chaos around her, including her abusive husband. While not physically capable of defending herself, she tries. She’s willing to defy her husband in order to save the lives of others. It’s a major step in the right direction as she transitions from victim to survivor. Her role models teach her what strength is through example. She learns to be strong rather than dependent.

Like me, Margaret relied her own strength and the support of others, something we should see more of in future fictional characters. Readers look for themselves in books, and as writers, it’s our job to give them that experience.

One Reply to “Portrayal of Victims in SF/F”